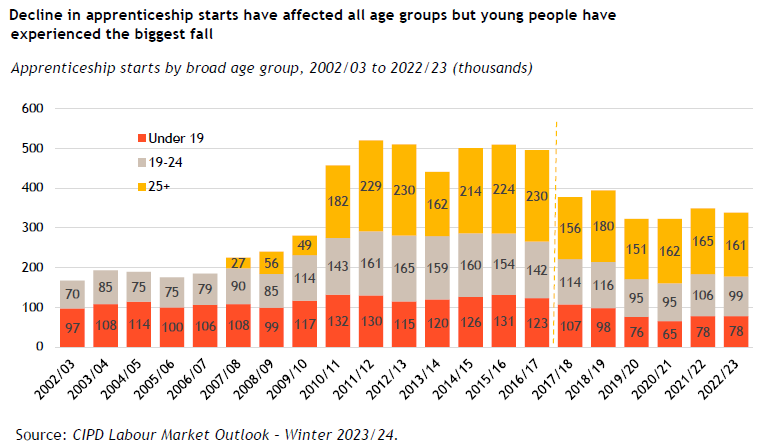

Look at the chart above, which shows UK apprenticeship starts, and you have to ask what went wrong in 2017, when they fall drastically. (The chart is from the CIPD who compile the data, by the way, and is included here with gratitude to the excellent Off to Lunch substack which used it a few days ago).

And something did indeed go wrong in 2017. The Government decided to ‘help’.

The logic was pretty clear. The UK, by and large, does not invest enough in training and developing people and that is likely to be a core driver of our fairly lacklustre national productivity growth over the last decade. That in turn leads to low economic growth, the persistent problem which has been at the heart of so much of our political and economic challenges.

Sensible, then, to try to do something to encourage businesses to invest more in training, and in particular in apprenticeships which are longer, more vocational and arguably more valuable than shorter courses.

And so the Apprenticeship Levy was born. The idea is that any larger employer (one who’s wage bill is greater than £3m a year) needs to set aside 0.5% of its wage bill for training schemes.

So far so good, but of course as it turned out the devil was in the detail. The training schemes which a business could fund using its Levy money were heavily regulated. A combination of the bureaucracy involved and the limitations on what kind of training would be approved has meant that most large employers have struggled to be able to ‘spend’ the amount they have paid in levies. Indeed The Times reports that over the last 5 years some £4.4bn raised through the levy has gone unspent. And that remember is, whatever you choose to call it, an additional tax on businesses.

It is no surprise, either, that retail businesses have been vocal amongst those suggesting that this policy has been a disaster and needs to change. The retail sector are big employers and, as we explored last week, training and motivating our colleagues is critical to our success. Even more frustratingly, many retailers (and other employers) are so committed to training and development that they are continuing to invest in training schemes of their own outside the Levy, having just written off the money that they have paid into the government scheme as unusable.

But be careful. As much fun as it is to throw rocks at politicians, there are lessons for all of us from the Apprenticeship Levy debacle.

What’s almost as interesting to me as the policy itself is the way those responsible have reacted to it and what that tells us as leaders about how we run our own organisations.

You’d think, wouldn’t you, that somewhere in the 7 years since the policy was launched and immediately had the opposite effect intended, that someone would have though “this is not working, we need to pull it and consider some different ways of achieving our objectives”. That does not, however, appear to be what has happened. The current Education Secretary, indeed, will assertively defend the scheme on the curious basis that the government is busy spending all the undrawn Levy money on training elsewhere (er, thanks?) and seems unmoved by the stark evidence of the graph we started this post with.

But let’s be honest, have you never done the same? Launched a new product line, found that it hasn’t resonated with customers but kept pushing it for longer than you should have on the basis that ‘it must come good eventually’? Hired a new senior colleague and gradually realised they aren’t right for the role, but held off for too long on acting because, let’s face it, you are embarrassed to have made the mistake in the first place? Started a big IT programme and watch horrified as wave after wave of budget overruns happen but feel like you are ‘in too deep’ to pull the plug?

I think we’ve all done one of those or something similar. So, at the same time as we ask nicely for the government to recognise that it has made a complete Horlicks of the Apprenticeship Levy and do something about it, let’s take a moment to look in the mirror and consider whether we have obvious mistakes of our own to fix too.

And while we are at it, let’s take a good look at the training and development we offer our colleagues today. Levy or no, it is becoming more and more the case that attracting the best talent is a key competitive battleground, and one on which you can’t afford to be left behind.

As a nation we really do invest too little in training, and as individual businesses we can often do more. Across the retail and hospitality sectors in particular we have a huge opportunity to act as engines of personal development - teaching people selling skills, leadership skills, and a long list of other skills that they will carry with them throughout their lives. The business which (a bit like Proctor and Gamble or Unilever in the product marketing world) becomes one that people are proud to have on their CV because of the excellence in training that it represents will find it much easier to attract the best people to work for it in the first place. Forward thinking businesses are working towards that already - are you?

P.S. This post is free for subscribers thanks to the generous support and partnership of the team at Barracuda Search.

Highly insightful application of the sunk cost fallacy and the psychology of admitting to failure. Matthew Syed's 'Black Box Thinking' provides countless examples of companies and crucially institutions failing to admit and learn from mistakes. Lets hope in the longer term the apprenticeship levy does not add to this sorry list.