You may have noticed that one or two movies have come out recently and that everyone is talking about them. It is indeed true that after a long fallow period the industry has an embarrassment of riches at the moment, with the hype around Barbie and Oppenheimer achieving the seemly impossible feat of eclipsing Tom Cruise and his Mission Impossible franchise.

The sector has been fairly starved of good news since the Covid pandemic began and so it is probably no surprise to see breathless headlines like this one across almost every media outlet:

So how do we square that with the grim realities of the financial performance of the sector? After all, Cineworld is basically bankrupt, Vue has been through a painful financial restructuring of its own which essentially wiped out its previous shareholders and AMC (owners of Odeon) have been held afloat only by entering the twilight world of the meme stock to raise and promptly burn through the cash of small-scale bubble-chasing investors.

Does the current excitement around this summer’s blockbusters mean all that pain is coming to an end? And why is it that cinema has struggled so much since the pandemic anyway when it feels like many other leisure sectors have rebounded?

For some answers, and also for some potential insight into other consumer sectors, we should turn to the economics.

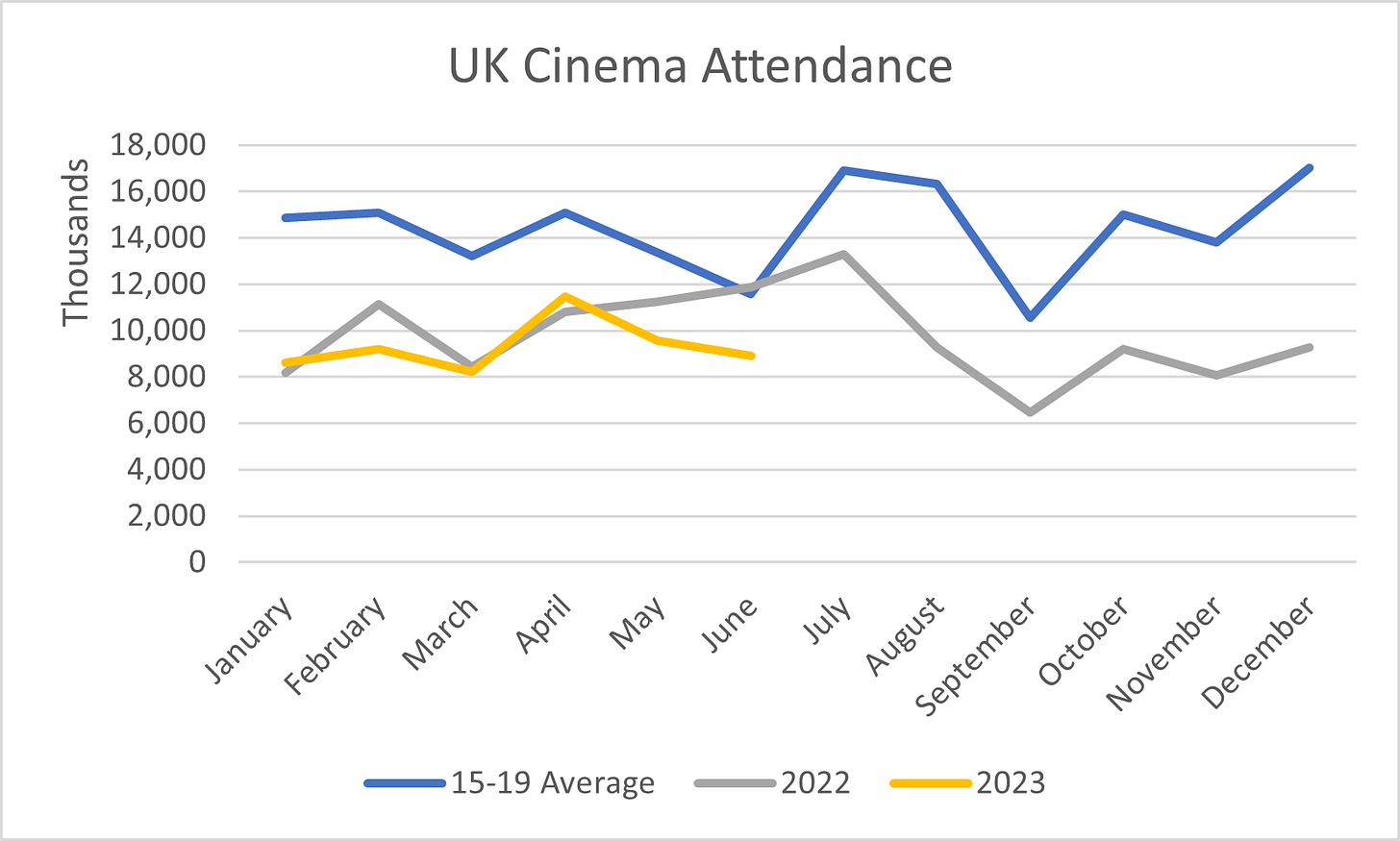

First of all, let’s look at the realities of how the sector has performed:

This chart shows the average monthly attendance at UK cinemas for the pre-pandemic period of 2015-2019, and compares that with what has happened in 2022 and so far this year. The picture is, I think, a fairly clear one - overall 2022 attendance was 68% of the pre-pandemic average and the picture in 2023 so far is similar but slightly worse (these figures are to June 23 and will see a boost from the last couple of weekends of blockbuster openings, of course).

In essence, the industry recovered to about 70% of its pre-pandemic performance and has, individual film openings notwithstanding, stayed at roughly that level ever since.

At some level, that isn’t bad - there are still millions of people going to the pictures every month.

But let’s put those figures through a model of a hypothetical chain of 50 multiplex cinemas to see what the current attendance means to profits. Here is the result of that using a model I built a few years ago which is no doubt a bit ‘finger in the air’ but is directionally accurate:

The key number we are looking at here is the admissions per screen, which drives a lot of the subsequent calculations. In the Base case, I used 35k admissions per screen per year, which was actually a bit below the 15-19 average which is more like 40k. Applying some assumptions about ticket prices and other revenues, applying a gross profit margin which is largely driven by the revenue sharing with movie distributors and then applying some fixed admin costs (head office, cinema rents etc) gets us down to a reasonable profit figure.

Conclusion so far: cinema, in the period pre-pandemic, was a good profitable industry.

But now we turn to the current scenario. The 2022 full year attendance of 117m represents more like 25k attendance per screen. Dropping that figure in at the top has the predictable effect of reducing the revenue and gross margin, and once we take off the fixed operational costs we get to the grim conclusion - this business is not profitable at this level.

Now there are a dozen ways to pick holes in this analysis. On the positive side, there will have been ticket and food and beverage revenue increases, both from price changes and from the fact that the smaller attendance figures will be made up from really enthusiastic film-goers.

It will also be the case, as is true in any business, that the “fixed” elements of cost are never really as fixed as you think and I’m sure that cinema operators will have been renegotiating lease terms with their landlords, reviewing staffing models and generally doing everything they can to manage those costs down.

But on the other side of the equation, it was also a painful truth of lockdown that the big studios used the opportunity to renegotiate their revenue shares with cinema chains. I have no idea by how much, but I doubt the net effect was a big win for the beleaguered cinema operators.

The Operational Gearing trap

So what? What do we conclude from this analysis?

Well one thing which would be a mistake to conclude is that there are no profitable cinema operators. Nothing could be further from the truth. In particular, those chains operating very up-market arthouse cinemas will have seen performance very different to this and indeed have been posting healthy profits and opening new sites. There will also be small, niche local operators with a strong customer base who are doing just fine.

But there is no mistaking the deadweight impact of those fixed costs on the big chains, and the impact is evident in their results.

And it is there that this stops being a story about cinema and becomes one relevantt o all of us, whatever kind of business we run. The balance in your costs between the easily variable and the largely fixed is called Operational Gearing and it is situations like the one the cinema operators find themselves in that it becomes important.

The more of your cost base is fixed, the more you are vulnerable to a relatively small drop in the volume of customers or in the value of the sales you make to those customers. Retailers, for example, don’t go bust because absolutely every customer decided to never shop there again. Instead they are dragged under by relatively small shifts - 10% of customers disappearing to online competitors, 5% of customers hit by a cost of living crisis and shopping less and so on. With high fixed costs of operation, those shifts have a much bigger impact on the profit line than they do on the revenue line and before you know it the administrators are in the car park.

So if you are going to think about something whilst you are queuing for your Barbenheimer tickets, think about the balance of fixed and variable cost in your business. How vulnerable does it leave you to a revenue downturn, and how might you re-engineer your business to reduce that risk and weather the storm? That’s a question that is well worth chewing on over your popcorn.

An interesting consideration in this P&L is the role of RPH. In the 2022/23 scenario, keeping everything else constant but increasing RPH to £3.50 turns EBITDA positive (albeit only to 3%). £4 gives 5.4%. Combine this with a bit of cost control and things look a lot better.

So lets consider the impact of price elasticity on the F&B products. Based on my visits to cinemas, operators have concluded there's low elasticity and hence £3+ for a small pouch of chocolates. But most people I know visit the nearest grocery convenience store and buy the pouch for £1, which would suggest higher elasticity. Knowing the true elasticity by product could drive up RPH - and might also improve gross margins through buying volume rebates.

Arca Blanca use data science to understand price elasticities and make price recommendations across large SKU ranges / locations / formats. Applicable to cinemas but even more relevant for retailers!

https://www.arcablanca.com/price-optimisation/