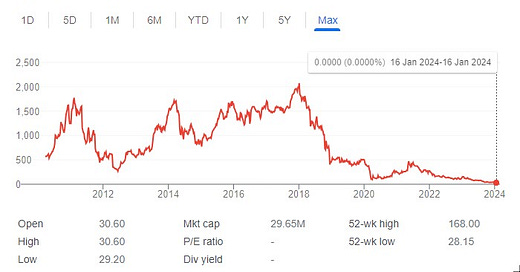

How’s that for a share price graph? Superdry has, it is fair to say, not been a terrific investment in recent years.

The key questions, though, are why the business has performed in this way and what lessons the rest of us can take from the story to apply to our own businesses.

For the sake of full disclosure, I’m not really a fan of either the brand or its retail execution, but personal taste to one side there is no denying that there is a lot to admire about Superdry. It built a strong brand identity that translates so clearly into its product range that they are instantly identifiable and it took that brand around the world through retail and wholesale partnerships - a rare example at one point of a UK originated brand conquering global retail.

So given those strengths, which both the founder Julian Dunkerton and the teams who have worked in the business over the years should be rightly proud of, why does the business now trade so poorly that it is valued on the stock market at less than the cash on its balance sheet?

Here are some possible explanations. Only those who have been inside the business over this period can tell the definitive story, but each of these issues is a plausible reason for the under-performance and each of them leaves us with useful watch-outs for our own businesses:

Psychodrama and distraction

Much has been written about the extraordinary story of the relationship between Superdry and its founder. Stepping down as CEO, leaving the business altogether to focus on other projects and then cannoning back through a fraught shareholder vote to rejoin as CEO in 2019 having very publicly derided the strategy being followed by the business.

A glance at the share price graph will show that this drama has not yet had a happy ending as the business has continued to struggle since. There is no denying Dunkerton’s passion for the brand but outside observers have to worry about how much turmoil all that corporate tension must have caused for teams across the business and whether that has made recovery easier or harder.

Founder-led businesses can be very binary ones. A mercurial leader with a clear vision who cuts though ‘steering committee’ noise and gets change done fast can be exactly what a business needs, but that’s only true as long as they can carry their colleagues, investors, suppliers and other stakeholders with them. Quick decisions are great, but only if they prove to be the right ones.

Over-expansion

By 2022, Superdry operated 220 stores across the world (99 in the UK and Ireland) and there were an additional 479 franchise and licensed stores alongside a bewildering array of global websites.

On the one hand, getting to that point over the previous years is a remarkable tribute to the value of the brand-building that had gone into creating Superdry.

On the other hand, it is an awful lot to manage, with the inevitable risks of distraction. Owned-store operations in far-flung places are a particular challenge (I have plenty of horror-stories of my own on this) as the level of detail and focus it takes to run a successful retail chain is hard to deploy over a long distance and big time-difference and in any case local market differences can make it hard to transfer lessons from one place to another.

Wholesale and partnership channels can offer an apparent solution to that, leaving much of the risk with third parties and allowing capital-light expansion across the world, but in fact the last couple of years for Superdry has shown that the Wholesale division has been the first to cause real problems, struggling to recover post pandemic and dragging the results of the overall group down sharply. The same lack of control and influence which made the channel so easy to expand quickly can come back to bite when a turnaround is needed.

The dangers of being a one-trick pony

Ask anyone about Superdry and what has gone wrong and an answer that quickly comes up is that its once-strong brand look has simply gone off the boil. A brand which attracted students and cool young types is now worn by their dads, with the inevitable toxic impact on the ‘coolness’ which once sustained the whole business.

There may well be truth to that, but I think it also illustrates a broader strategic point. If you are too dependant on a single look, a single product or a single supplier then your business is inevitably riskier than one that has a broader base.

There are haunting similarities between the current path being followed by Superdry and that of Cath Kidston, for example - a brand built on a strong but very individual look which expanded dramatically around the world but ultimately collapsed under its own weight.

And that is not just true of businesses with a narrow design-base. When I ran Game, investors used to point out occasionally that pretty much everything we sold came from three suppliers (Microsoft, Nintendo and Sony) and history would show that that implied weakness was right on the money - it only took a couple of those suppliers to delay their product launch by a year and our whole business collapsed.

Just as there is value in diversification of an investment portfolio, there is value in diversification for an individual business of its key ranges and suppliers.

(Regular Moving Tribes readers will recall a recent post about Oliver Bonas which celebrated that business has having a single-minded focus on a particular customer segment and being successful as a result. How do we reconcile that with this observation that too narrow a business can be too risky? That’s a fascinating topic we will explore in the coming weeks).

The slippery slope

Spend a bit of time looking at Superdry results statements and what stands out more than anything is not the long term progress of the business but its short term issues.

Look at the full year to April 23, for example, and retail growth was something like 14%. Overall revenue growth was only 2% because of those issues in the wholesale division but you might have been persuaded that the store figures at least proved that the brand was still viable, was recovering from pandemic disruption and that there might indeed be a path forward.

However. Look at the ‘current trading’ bit of that announcement and store sales for the first quarter (May-September 23) of FY24 were actually down 3.7% over the prior year - so a huge downturn from the 14% growth the business had been seeing.

Run forward to the half-year statement and it gets worse - for the first half in total to end October 23, stores and ecommerce together are now down 13% year over year, with wholesale still collapsing too.

The ‘current trading’ bit of that announcement was a bit better at only -7% but the language around it was unmistakably pessimistic. I write this before the Christmas trading statement comes out, so fingers crossed but a major turnaround feels unlikely.

In all of those statements the ‘corporate excuse factory’ is in full swing, blaming the weather, the economy and even in one fabulous article blaming the American Candy stores on Oxford Street. But there is no avoiding the fact that these negative results in 2023 sit alongside competing retailers like Next, Fat Face and White Stuff who were in strong positive growth.

So what has gone so wrong in this last year? The clue may well be in that first full year statement to April 23. Although the revenue figures are not bad, look further down and there are some worrying phrases being used like “material uncertainty” related to the businesses ability to continue to trade. (The phrase ‘material uncertainty’ is used 15 times in the results press release, which is never encouraging).

What does that mean? In a nutshell, the business is running out of money. It has taken on new debt, issued new shares at a very low price, sold its brand in Asia-Pacific and is cutting costs as fast as it can, as the years of trouble in the Wholesale division take their toll on the balance sheet.

That’s entirely the right thing to do, but anyone who has done it will tell you it is very difficult to be in full-scale cost-cutting and cash-management mode and still trade well. There is huge distraction for the management team, things like IT programmes, store maintenance and other ‘investments’ get cut and finally even things like hours in store get chopped back - all with a potential negative impact on performance.

Looking forward

So what does the future hold? I hope for the best, it is fundamentally a good brand and a lot of terrific people work in the business. Marrying an essential financial turnaround, though, with the kind of focus necessary to bring trading levels back up to those being delivered by competitors is a tough challenge. Our High Streets would be lesser without them, though, so here’s hoping they can find a way through.

In amongst many nuggets here, the founder/family one chimed with me. A couple of the businesses I've worked with have seen a similar dynamic. The one with the largest impact (In ££) was Matalan. My understanding was that the family connections to their supply base was critical during Covid (when orders had to be cancelled) but there had to be a way to help suppliers stay afloat, and maintain relationships. But...in a tough market, first generation founder skills can leave the business short on options once a certain mass has been achieved. And founders find it hard not to keep coming back in to get rid of CEOs and Commercial Directors who are trying to modernise. As a business grows, it is important that organisational capability rises with it (People, IT, Processes, Distribution/Logistics etc.) Three areas as examples: 1. A lack of investment in systems can leave a business critically hamstrung - something you talked about in last week's omnichannel post. Not being able to move your stock between channels, or know how best to allocate by store and channel can lead to unnecessary out of stocks and extra markdowns, for instance. Or not really having reliable stock figures at all! 2. A lack of investment in people means you can have lots of over-promoted internal colleagues, and lots of long-servers sticking to ways of working that don't look outwards to the customer base. Fresh blood can bring experience that can fast-track wins for customers, colleagues and shareholders. 3. Delivery promises to customers. You have a 3 to 5 day promise you make when your competition is delivering in 1 to 3 days. And maybe that's because you have to wait for overnight IT batch processes, and because your picking of store and online channels is a bit different, or requires a lot more walking in the warehouse that was designed for analogue stores. All of the substantial issues could be faced into by a brilliant Board, but they need to get a wiggle on, particularly as it is fashion, and because that cash outflow is worrying. Great article, thank you for sharing.