This year, as in most, the fantastic team at Retail Week have produced a league table of Christmas trading performance, which you can read here .

There is a wide range of performance reflected in the table, though personally a couple of the very positive numbers at the top of the table look a bit odd to me and warrant some further digging, which may lead to a future post.

The fact that many of the ‘like for like’ revenue growth numbers are positive has prompted a general reaction of “phew, maybe things aren’t so bad after all?”. But whether you are an investor in, observer of, or operator in the retail sector, there are a few things to bear in mind when you look at that league table.

Unaudited

The operating word applicable to most Christmas trading statement press releases is ‘unaudited’. These statements are not part of the formal reporting cycle that companies have to provide and represent only a snapshot of a few selected metrics.

Now that’s not to say that anyone is going to wilfully mislead in their trading statements, and directors would doubtless get into some trouble if they did so, but there is inevitably a big difference between some numbers pulled out of internal reporting systems for a few weeks in the run-up to Christmas and the properly audited and externally validated financial statements covering the same period, which will usually come out many months later.

For public companies (those floated on the stock market) the rules are a bit tighter, to be fair, because they also have an obligation to update the market if their view of the profit they will generate for their current financial year changes by more than a small amount. That is the obligation that generates every financial journalist’s favourite story, the ‘profit warning’, where a company is forced by current trading to indicate that the current range of analyst forecasts of its profit for the year is unlikely to be met.

That means that for observers of publicly traded retail businesses the most interesting bit of the trading statement is the reference (if any) to that consensus profit forecast. “We had huge LFL sales growth” is a great headline but if further down the release it says “and our profit projections remain in the middle of the current market consensus” then the story becomes a little different.

What’s in a name?

One of the reasons that trading statements can be so difficult to read (and even harder to compare between companies) is that the definitions used can be pretty woolly. One obvious challenge is that the time periods being measured are often all different. One business will use “the 12 weeks up to Christmas”, another will use 6 weeks but also include the first week after Christmas and so on.

But even if you can line up time periods, what exactly is it that is being reported? Usually “Like for Like” sales growth but what does that mean? Which stores are being included or excluded from the measure? Obviously ones which weren’t trading last year will be excluded, but what about stores that have had a big refit? Or ones which are currently in a closing down sale? Without an audited standard definition, there are a host of ways to make an LFL figure look better or worse.

And that was just within store sales. In the overall LFL, are e-commerce sales included or not? If a split between e-commerce and store sales is made, where are click and collect sales being counted?

There are no right or wrong answers to these questions, but what they create is a significant degree of uncertainty about what the figures really mean.

Revenue is not profit

Above all, though, we need to be mindful of what the statements are talking about, which is almost certainly only revenues. With the exception of the profit guidance from PLCs we’ve already discussed, it is quite likely that there are no margin or profit figures in a trading statement, for the very good reason that the business has probably not finished preparing its P&L for the period at the point where the figures are reported.

When reading a trading statement, bear in mind the old saying that “turnover is vanity, profit is sanity” and that’s one to bear in mind when reading a trading statement. The real story of how a business performed over its peak period will only come out months later when the accounts are properly prepared. Not only are margin and profit vital elements to understand about a company’s performance, but several key ingredients of those measures may not even have happened by the time you are reading the trading statement - what about customer returns, for example, particularly from e-commerce sales?

Inflated expectations

The importance of understanding the difference between revenue and profit is particularly acute this year.

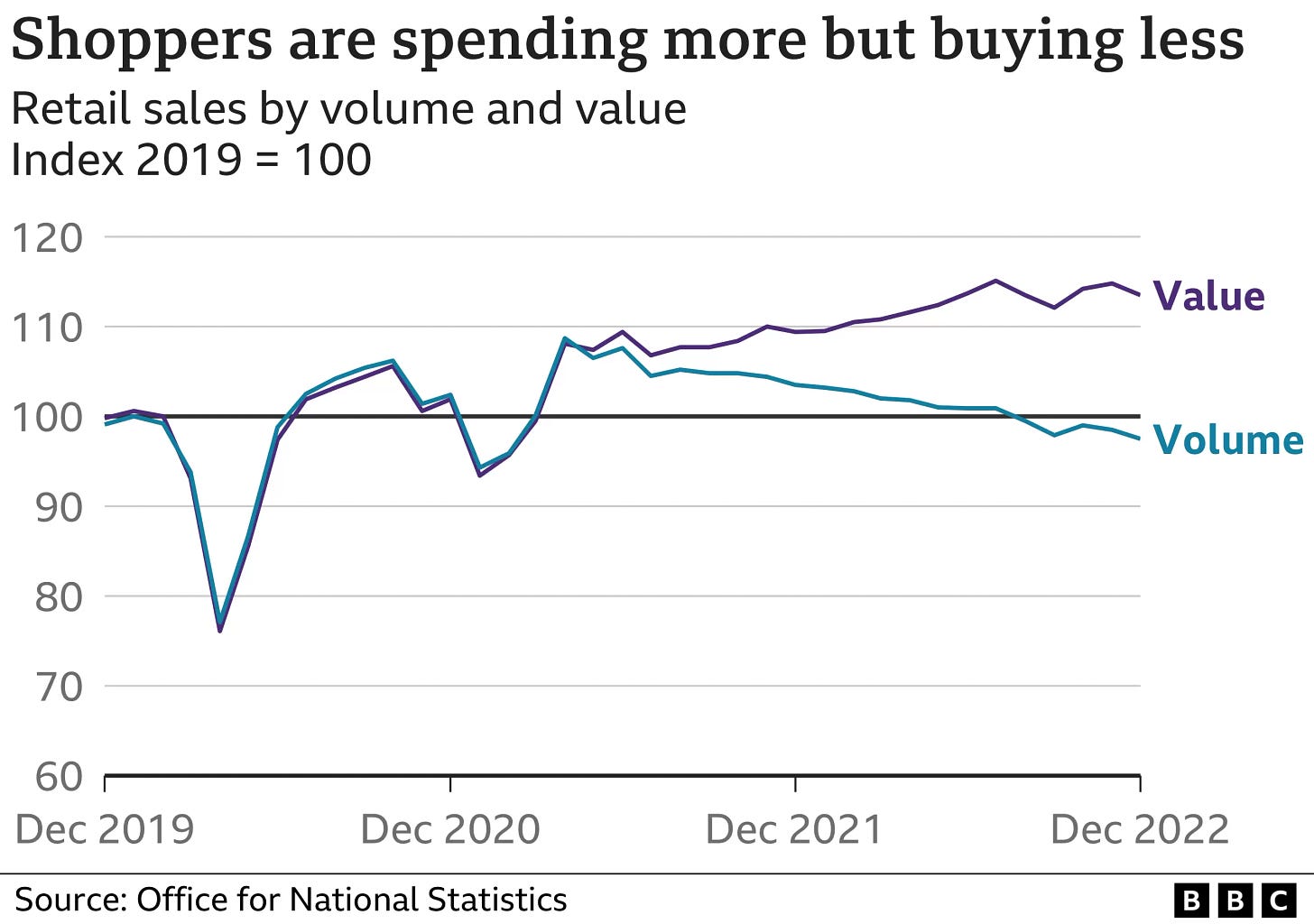

Look at the Retail Week table, and draw a line about half way down at 10% positive revenue growth. That, of course, was where inflation was running during peak trading this year - so anyone below that number, even if their revenue growth was positive, has either sold fewer products at higher prices or radically changed the mix of what they sell altogether.

And all of that makes it even harder to read the profit impact of performance. If you’ve sold 5% fewer products at 15.8%1 higher prices to get your 10% revenue growth, what happened to your input costs? If you’ve held them to 15.8% or less then you are probably in a good position, but if they’ve gone up by more than you could raise your consumer prices (as many raw materials have, for example) then your margin and total profit generated might well have dropped sharply.

ONS figures, which you can read here illustrate that this dynamic of falling volumes and rising prices will indeed be one impacting many retailers, as overall sales volumes fell in December even though revenues rose.

As such, the real story of the winners and losers over the Christmas period will be told not by LFL sales figures, but by input costs, gross margins and the profits they generate. More than ever, this will be a period where successful buying and category management will be at least as big a driver of the end result as successful selling.

Indeed, I suspect that there are some businesses quite low down in the simple LFL league table who may end up having performed better than expected at an underlying profit and cash level, whilst there may also be some further up who disappoint when the full picture emerges.

All that glitters..

P.S.

Sharp eyed readers of the newsletter will have noticed that the retailer I chair, Bensons, is present in the Retail Week league table I’ve linked above. That gives me my first, and hopefully last, opportunity to add an important disclaimer to Moving Tribes - I’m not not, nor will I ever, be commenting on any business I’m personally involved with, either explicitly or implictly - so there are no clues to Bensons performance (intentional or otherwise) in this post!

P.P.S.

If you enjoyed reading this, terrific. If it inspires you to say something, please do comment below or email me directly. And if you want to support Moving Tribes, then hands-down the most helpful thing you can do is to share a link to this post with everyone and anyone you know - via email, on social media or wherever suits you. There’s even a button to help you do it!

Cheers

Ian

Consider this a bonus personality test from this first Moving Tribes post - are you one of the people who just believed that 15.8% number, or one of those who immediately got your calculator out and are no doubt drafting a comment about it already??